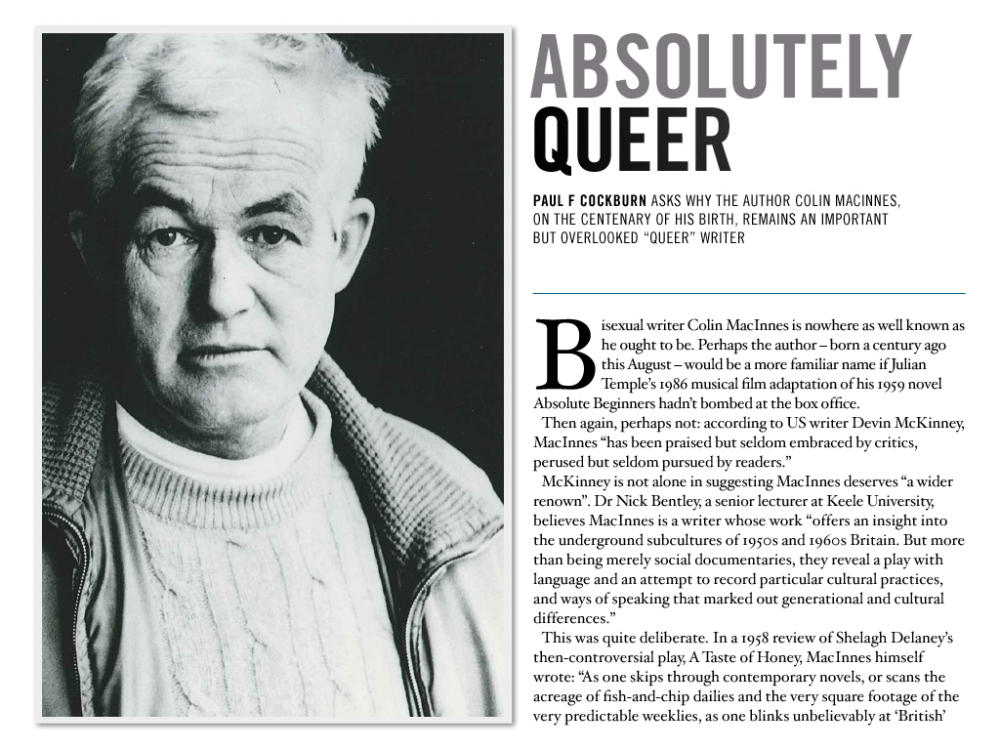

Colin MacInnes is nowhere as well known as he ought to be. Perhaps the author–born a century ago this August–would be a more familiar name if Julian Temple’s 1986 musical film adaptation of his 1959 novel Absolute Beginners hadn’t bombed at the box office. Then again, perhaps not: according to US writer Devin McKinney, MacInnes “has been praised but seldom embraced by critics, perused but seldom pursued by readers.”

McKinney is not alone in suggesting MacInnes deserves “a wider renown”. Dr Nick Bentley, a Senior Lecturer at Keele University, believes MacInnes is a writer whose work “offers an insight into the underground subcultures of 1950s and 1960s Britain. But more than being merely social documentaries, they reveal a play with language and an attempt to record particular cultural practices, and ways of speaking that marked out generational and cultural differences.”

McKinney is not alone in suggesting MacInnes deserves “a wider renown”. Dr Nick Bentley, a Senior Lecturer at Keele University, believes MacInnes is a writer whose work “offers an insight into the underground subcultures of 1950s and 1960s Britain. But more than being merely social documentaries, they reveal a play with language and an attempt to record particular cultural practices, and ways of speaking that marked out generational and cultural differences.”

This was quite deliberate: in a 1958 review of Shelagh Delaney’s then-controversial play, A Taste of Honey, MacInnes himself wrote: “As one skips through contemporary novels, or scans the acreage of fish-and-chip dailies and the very square footage of the very predictable weeklies, as one blinks unbelievably at ‘British’ films and stares boss-eyed at the frantic race against time that constitutes the telly, it is amazing—it really is—how very little one can learn about England here and now.”

Colin MacInnes was the son of a professional singer James Campbell McInnes and the novelist Angela Mackail, through whom he could claim family links with former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and The Jungle Book author Rudyard Kipling. Thanks to McInnes’s bisexuality, the marriage didn’t last; they divorced and, for a time, Mackail with a new husband and her children moved to Australia. By the 1930s, however, they had returned to London, with MacInnes studying painting, while also reverting to using his birth father’s surname–albeit with an additional “A”.

Following the Second World War, during which he served as a sergeant in the Intelligence Corps, MacInness joined the BBC as a script-writer; by the 1950s, however, he was supporting himself by writing essays, plays, and novels. These include pirate parody Westward to Laughter (1969) and Three Years to Play (1970), set in the world of Elizabethan drama; when he died, in April 1976, MacInnes was writing Angus Bard, based on his father’s early life.

Of course, MacInnes’s most famous works are his ‘London Trilogy’ of novels: City of Spades (1957), Absolute Beginners (1959) and Mr Love and Justice (1960). Bentley believes they leave no doubt about MacInnes being as much an “Angry Young Man” as Alan Sillitoe, David Storey and John Osborne; and as much a part of New Wave British Realism as Karel Reisz’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning or Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey.

Yet MacInnes was still very much his own man. “Firstly, the emphasis for him was nearly always London, where the Angries and the New Wave tended to be set in provincial northern towns,” Bentley points out. “Secondly, MacInnes focused on characters from a much broader set of marginalised positions than the focus on the white working class in the Angry and New Wave work—including African, Caribbean and Jewish characters, lesbian and gay characters, and a range of youth subcultures such as jazz fans, teenagers, Teddy boys and Beatniks.”

Bentley includes Absolute Beginners on his second year undergraduate course on youth subcultures in fiction and film. “In fact it’s the first text we look at, which shows how much of a groundbreaker MacInnes was,” he says. “The students seem to really enjoy it, although I guess they see it as more of a historical piece now–most of them, of course, being born in the mid 1990s!

His work is still seen as on the margins of the literature of the period, but the London Trilogy is quite often referred to in relation either to work on 1950s literature generally, or studies of fiction/film that that look at the representation of youth subcultures.”

Like his father before him, MacInnes, was bisexual–indeed, three years before his death, he published Loving Them Both: Study of Bisexuality and Bisexuals, though it’s impact both academically and more generally would appear to be extremely limited. Yet Bentley believes that MacInnes’s sexuality shouldn’t be ignored. “His bisexuality is almost certainly driving his interest in the subcultural and marginalized groups in London during the period,” he insists.

“He was clearly attracted to what was in the 1950s and 1960s a seedy undergrounds of London, particularly Soho, with its wide range of sexualities and ethnicities,” Bentley adds. “The LGBT characters in MacInnes’s novels, however, are not there merely because they represented a sense of alternative cultures in the 1950s; they appear as fully rounded individuals who sit naturally in his urban landscapes.”

First published by Pride Life (Summer 2014).