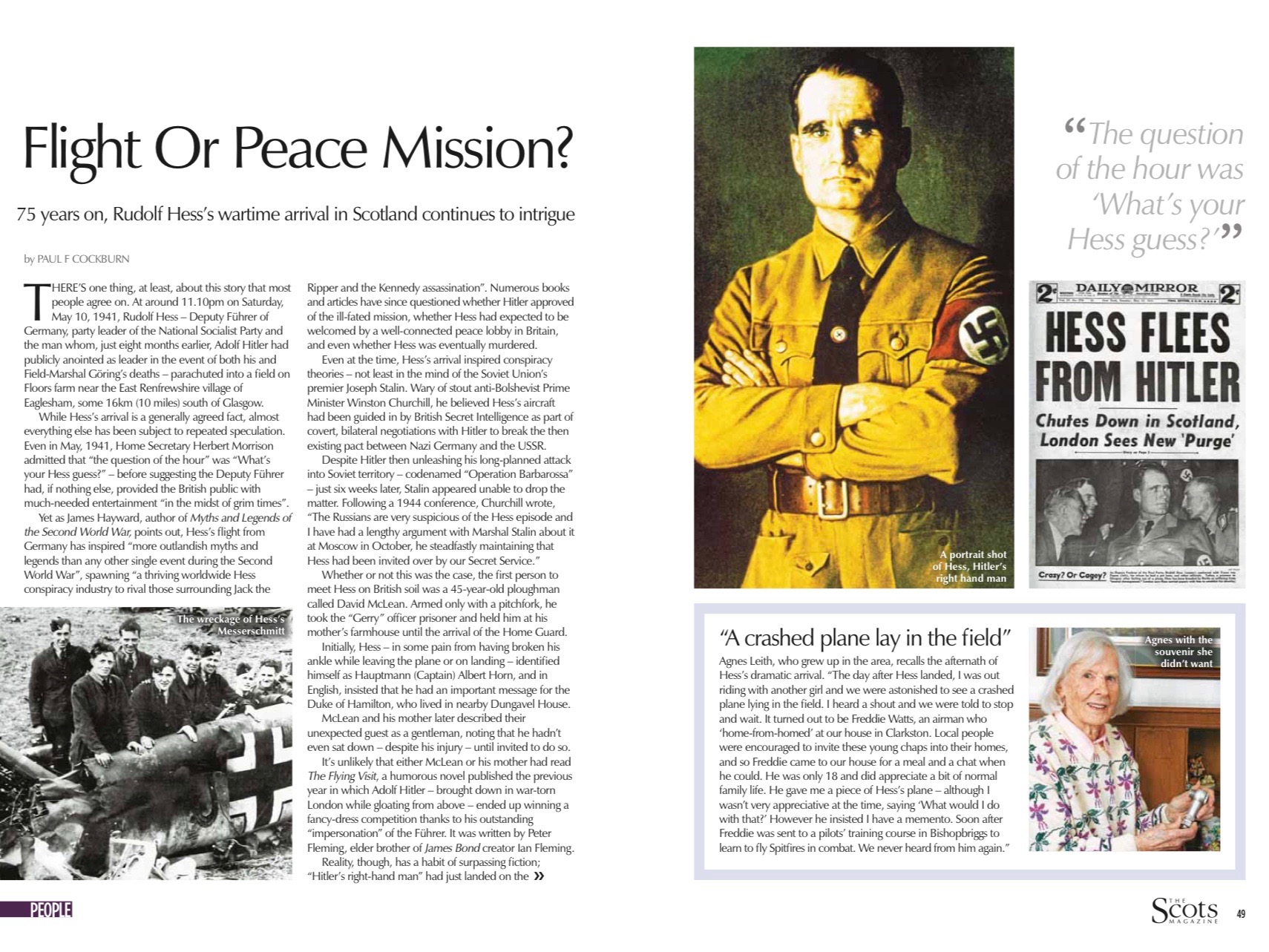

There’s one thing, at least, that most people agree on. At around 11.10pm on Saturday 10th May 1941, Rudolf Hess – Deputy Führer of Germany, Party leader of the National Socialist Party and the man whom, just eight months earlier, Adolf Hitler had publicly anointed as leader in the event of both his and Field-Marshal Göring’s deaths – parachuted into a field on Floors farm near the East Renfrewshire village of Eaglesham, some 10 miles south of Glasgow.

While Hess’s arrival is a generally agreed fact, almost everything else about it has been subject to repeated speculation. Even back in May 1941, Home Secretary Herbert Morrison admitted that “the question of the hour” was “What’s your Hess guess?” – before suggesting that the Deputy Führer had, if nothing else, provided the British public with some much-needed entertainment “in the midst of grim times”.

Yet as James Hayward, author of Myths and Legends of the Second World War, points out, Hess’s flight from Germany has inspired “more outlandish myths and legends than any other single event during the Second World War”, spawning “a thriving worldwide Hess conspiracy industry to rival those surrounding Jack the Ripper and the Kennedy assassination”.

Numerous books and articles have since questioned whether or not Hitler approved of the ill-fated mission, whether Hess had expected to be welcomed by a well-connected peace lobby in Britain, and even whether Hess was eventually murdered.

Even at the time, Hess’s arrival inspired conspiracy theories, not least in the mind of the Soviet Union’s premier Joseph Stalin. Wary of stout anti-Bolshevist Prime Minister Winston Churchill, he believed that Hess’s aircraft had been guided in by British Secret Intelligence, as part of covert, bilateral negotiations with Hitler to break the-then existing pact between Nazi Germany and the USSR.

Despite Hitler then unleashing his long-planned attack into Soviet territory – code-named “Operation Barbarossa” – just six weeks later, Stalin appeared unable to drop the matter. Following a 1944 conference, Churchill wrote: “The Russians are very suspicious of the Hess episode and I have had a lengthy argument with Marshal Stalin about it at Moscow in October, he steadfastly maintaining that Hess had been invited over by our Secret Service.”

Whether or not this was the case, the first person to actually meet Hess on British soil was a 45 year-old ploughman called David McLean who, armed only with a pitchfork, took the “Gerry” officer prisoner and held him at his mother’s farmhouse until the arrival of the local Home Guard. Initially, Hess – in some pain from having broken his ankle while either leaving the plane or on landing – identified himself as Hauptmann (Captain) Albert Horn, and in English insisted that he had an important message for the Duke of Hamilton, who lived in nearby Dungavel House.

Both McLean and his mother later described their unexpected guest as a gentleman, noting that he hadn’t even sat down – despite his injured ankle – until invited to do so.

It’s somewhat unlikely that either McLean or his mother had read The Flying Visit, a comedy novel published the previous year in which Adolf Hitler – unexpectedly brought down in war-torn London while gloating from above – had ended up winning a fancy-dress competition thanks to his outstanding “impersonation” of the Führer. (This humorous example of wartime propaganda was written by Peter Fleming, elder brother of James Bond creator Ian Fleming.)

Reality, though, has a habit of out-weirding fiction; “Hitler’s right-hand man” had just landed on the McLean’s doorstep. It was only following a sudden influx of army trucks and policemen, the latter ordering everybody to stay indoors until told otherwise, that local people had any suspicions about their recent visitor’s real significance.

Hess was officially arrested by members of the 1st Renfrewshire & Bute Battalion of the Home Guard, and taken back to their HQ, a Scout Hall in Giffnock. Roman Battaglia, a German-speaking clerk from the Polish Consulate in Glasgow, invited by the Home Guard to aid questioning, gained little additional information – although some insist this was when Hess first admitted his real identity. In any case, Hess was soon transferred into the care of the British Army and held overnight in the guard house of Maryhill Barracks, Glasgow.

At the Prime Minister’s insistence, Hess was subsequently moved south – spending four days in the Queen’s House within the Tower of London – the last prisoner to be held there. Hess was subsequently moved to a specially-created Camp Z in Aldershot, and would later spend the rest of the war in facilities in Buckinghamshire and Abergavenny, South Wales.

During his initial “debriefing”, Hess insisted that his mission was a personal attempt to broker a peace between Britain and Germany, two Anglo-Saxon nations which he strongly believed should not be at war. However, the Deputy Führer was quickly rebuffed as an embarrassment by the British Government – “Nazi gangster” being among the more sober public descriptions made by numerous Cabinet ministers in the days that followed the official confirmation of his presence on the British mainland.

“It doesn’t matter what kind of animal he is,” explained Herbert Morrison on the Saturday following Hess’s arrival and arrest. “Whether he is Rat No. 1 or a Trojan horse, or just a giant panda over here in the vain hope of finding innocents to play with – the main thing is that he is caged.”

The Nazi regime, it should be pointed out, were even faster off the mark that the British authorities, broadcasting initial announcements within two days that cast doubts about the Deputy Führer’s mental health and suggested that he may even have experienced “hallucinations” before embarking on his flight.

In any case, any minuscule chance of there being a positive response to Hess’s overtures was firmly dashed the evening of his flight. The clear sky and full moon which had aided his navigation to Scotland also enabled more than 500 Luftwaffe bombers to launch an unprecedented massive assault on London. The night’s bombing claimed 1,486 lives, destroy 11,000 homes, and damaged several landmark buildings including the Houses of Parliament, Waterloo Station, and the British Museum.

While the likes of Sir Henry Morris-Jones MP saw Hess’s flight as “the first beam of light in a very dark world,” the then Private Secretary to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lieutenant-Commander Fletcher, suggested caution. “This is the time of year when rare migrant birds arrive in these islands for breeding purposes,” he pointed out. “A very strange one has certainly arrived in Scotland. He may be a swallow or a cuckoo, but one swallow does not make a summer, and the cuckoo, in spite of the simple and ingenious notes of its call, has a sinister side to its character.”

After the war, Hess was convicted of crimes against peace by the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal in 1946. He was subsequently held as Prisoner No. 7 at Spandau Prison in Berlin. Repeatedly denied parole, in part thanks to Soviet intransigence, the 93-year old Hess died – possibly at his own hands – on 17 August 1987.

Part of the wreckage of Hess’s aircraft is held by the National Museum of Flight at East Fortune.

First published in The Scots Magazine, May 2016.