The Scots Magazine has long prided itself in being at the forefront of everything “Scottish”, so it’s surely no surprise that, in June 1817, the writer of the magazine’s then-regular “Literary Intelligence” column was pleased to report: “A new Novel, entitled Rob Roy, is announced from the pen of the Author of Waverley.

The Scots Magazine has long prided itself in being at the forefront of everything “Scottish”, so it’s surely no surprise that, in June 1817, the writer of the magazine’s then-regular “Literary Intelligence” column was pleased to report: “A new Novel, entitled Rob Roy, is announced from the pen of the Author of Waverley.

“The exploits of that celebrated freebooter,” they went on, “affords a subject so admirably suited to the genius of their admirable writer, that this work is expected even to surpass in interest those which he has hitherto produced.”

There was certainly a lot of interest in the novel; when finally published in Edinburgh—originally anonymously, at the end of December 1817—the original print run of 10,000 copies (itself a huge figure for the time) sold out after two weeks. At one point, a ship bound for London sailed out from Leith with nothing but copies of Rob Roy filling its hold.

Some sixty years later, another much-loved (and, like Scott, Edinburgh-born) author happily confirmed the book’s literary merits. In an essay of “random memories” about childhood and books, Robert Louis Stevenson wrote of Rob Roy: “I dare be known to think it the best of Sir Walter’s by nearly as much as Sir Walter is the best of novelists.”

So whoever compiled that Literary Intelligence column in 1817 certainly had their finger on the pulse of the publishing world; not least because Scott had only just signed a contract for the novel (with the Fife-born publisher Archibald Constable) in May—presumably around the time when the June issue of The Scots Magazine was being “put to bed”.

The announcement, however, was arguably premature: Scott didn’t start writing the novel until August, following a “research trip” to Rob Roy’s Cave, on the banks of Loch Lomond, which legend suggests the real Rob Roy MacGregor used as a hide-out during his cattle-rustling years.

To make matters worse, that autumn Scott came down with a recurring gallstone-related illness; he was forced to take high quantities of the narcotic painkiller laudanum, while also dieting to the point of starvation. He kept writing, though—producing one of his most accessible novels, which helped confirm that his prose was now eclipsing the verse narratives with which he had made his name.

Inspired by the folk legends surrounding the infamous reiver who, in the early 1700s, nevertheless showed kindness to the poor and disadvantaged—hence the writer’s description of him as “the Robin Hood of Scotland”—Scott set his novel a century back, just before the outbreak of the first Jacobite rising in 1715. Now twice that time-span on from the novel’s publication, there are admittedly aspects which can easily puzzle present-day readers.

The most obvious of these is that, while titled Rob Roy, the novel’s first-person narrator and principal protagonist is actually Francis “Frank” Osbaldistone, the son of an English merchant who travels first to Northumberland and then (in the latter half of the novel) the Scottish Highlands in order to recover financial documents stolen from his father.

The titular Rob Roy MacGregor—while a memorable, larger-than-life character—initially appears only briefly and somewhat mysteriously. Nevertheless, Scott’s portrayal—of Rob Roy as an honest and upright Highland gentleman who has been forced, by circumstances, into a life of blackmail and robbery, has proved influential.

To the immense benefit of Scott’s literary career, the initial critical response to Rob Roy was almost unanimously positive. When it came to creating characters, Scott was compared with William Shakespeare; with Rob Roy, particular praise was reserved for Frank’s shrewd but cowardly manservant, Andrew Fairservice.

A rare contemporary criticism, however, was published in the Edinburgh Review, a magazine for which Scott himself wrote; the Scottish judge and reviewer Francis Jeffrey argued that Scott’s portrayal of Diana Vernon (a young Northumberland lady who becomes the focus of Frank’s romantic intentions) was unbelievable, given the North of England society in which she grew up. Most readers, however, disagreed—enchanted, no doubt as much as Frank, by the character’s beauty and intelligence.

Two centuries on, this influential historical novel remains an intriguing adventure, which look at the build-up to the Jacobite rising and the tensions existing between England and Scotland over the Union. For that reason alone, it’s arguable that Scott’s Rob Roy still has real relevance today.

ROB ROY ON THE BIG SCREEN

All three Rob Roy films are inspired by the historical figure, rather than Sir Walter Scott’s novel.

Rob Roy (1922): Produced by Gaumont British Pictures Corporation, and directed by W P Kellino, this silent movie starred then-popular British actor David Hawthorne as Rob Roy MacGregor. With a running time under 20 minutes, the screenwriter–the playwright Alice Ramsey—understandably simplified his story: “A clan chief seeks revenge on the jealous Duke who outlawed him.”

Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue (1953): Dublin-born, Devon-raised Richard Todd starred in this colourful Walt Disney film, filmed in Scotland with a cast including the formidable James Robertson Justice (as the sympathetic Duke of Argyll) and numerous extras belonging to the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, just returned from active service in Korea. Todd had previously played Robin Hood for Disney.

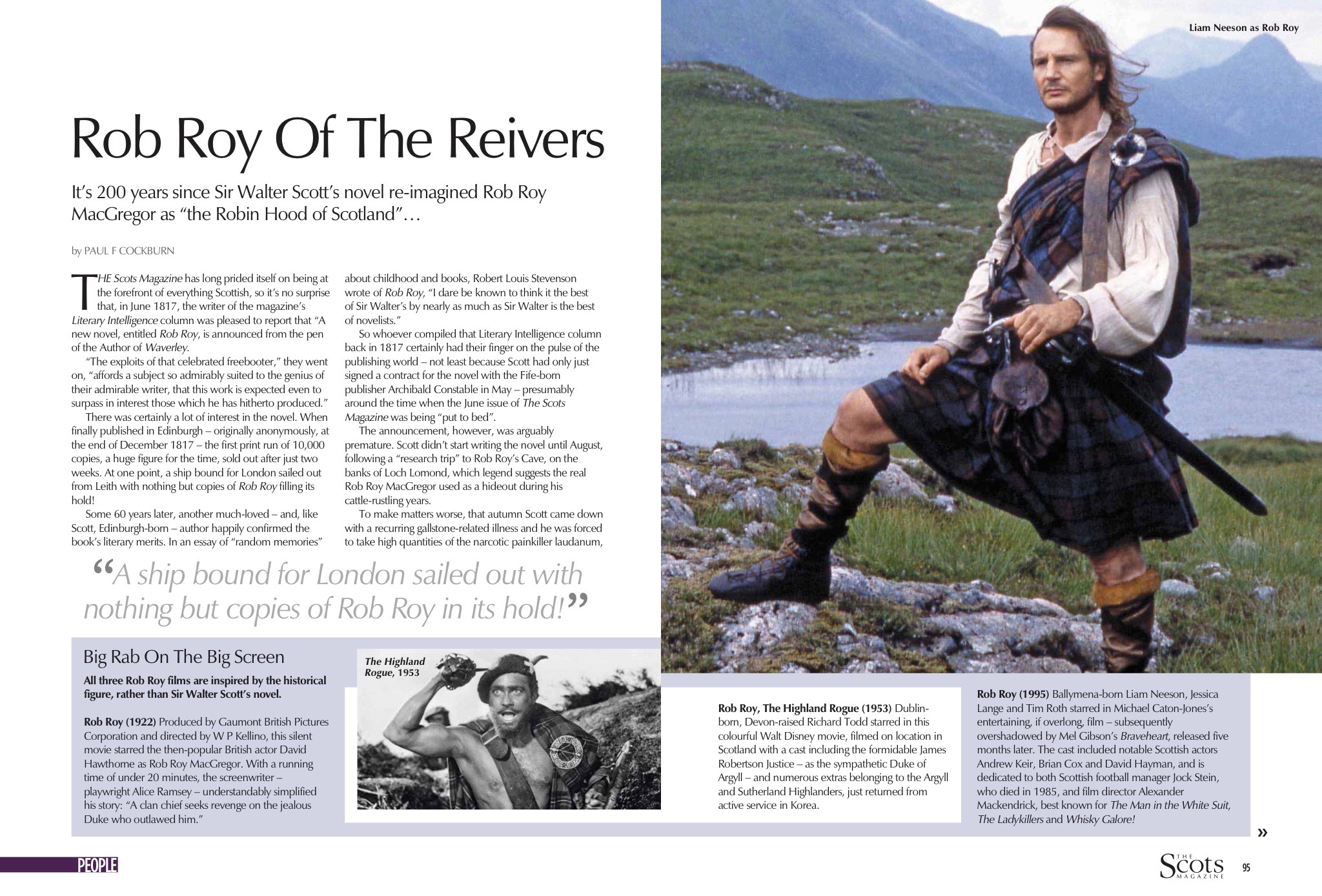

Rob Roy (1995): Ballymena-born Liam Neeson, Jessica Lange and Tim Roth starred in Michael Caton-Jones’s entertaining, if overlong, film—subsequently overshadowed by Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, released five months later. The cast included notable Scottish actors Andrew Keir, Brian Cox, and David Hayman, and dedicated to both Scottish football manager “Jock” Stein (who died in 1985) and film director Alexander Mackendrick, best known for The Man in the White Suite, The Ladykillers, and Whisky Galore!

DID YOU KNOW?

Rob Roy Films, the company set up by producer Peter Broughan to make Rob Roy in 1995, continues to make documentaries and films. Currently in development are a new adaptation of Macbeth, and Paradise—described as “Gangs of New York meets Field of Dreams in Victorian Glasgow”.

First published in The Scots Magazine, #June 2017.