As we strive to explore and expand beyond the sphere of our own planet, we’re leavng a growing trail of artefacts with vital cultural significance along the way. Should we preserve our space history – and how?

As we strive to explore and expand beyond the sphere of our own planet, we’re leavng a growing trail of artefacts with vital cultural significance along the way. Should we preserve our space history – and how?

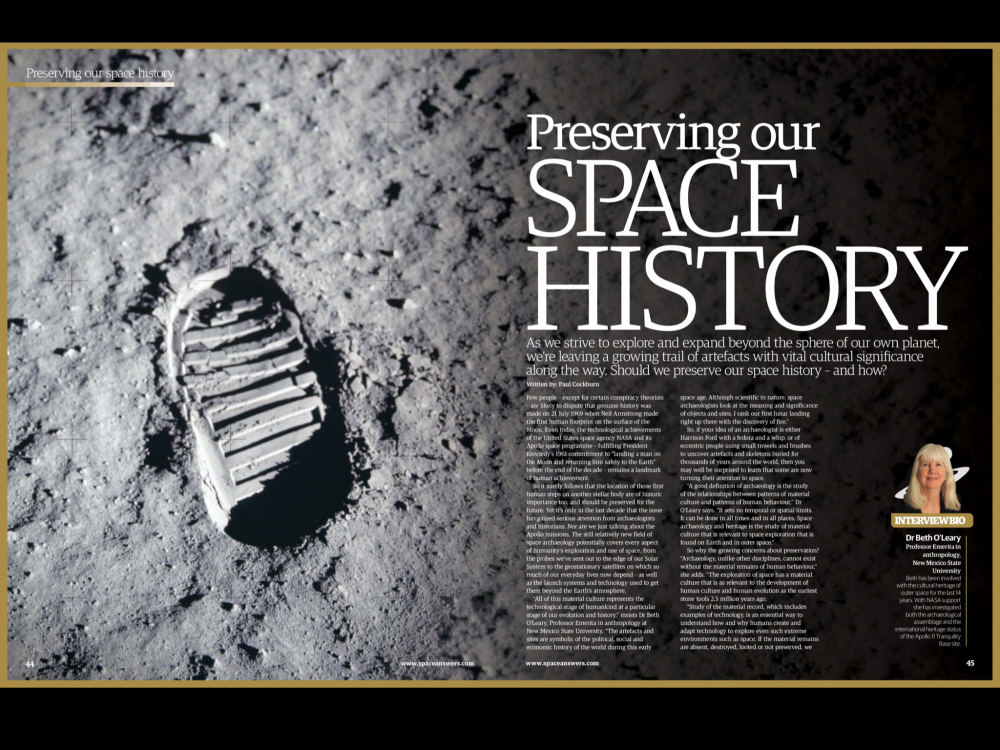

Few people—except for certain conspiracy theorists—are likely to dispute that genuine history was made on 21 July 1969 when Neil Armstrong made the first human footprint on the surface on the Moon. Even today, the technological achievements of the American space agency NASA and its Apollo space program—fulfilling President Kennedy’s 1961 commitment to “landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth” before the end of the decade—remains a landmark of human achievement.

So it surely follows that the location of those first human steps on another stellar body are of historic importance too, and should be preserved for the future. Yet it’s only in the last decade that the issue has gained serious attention from archaeologists and historians. Nor are we just talking about the Apollo missions. The still-relatively new field of space archaeology potentially covers every aspect of humanity’s exploration and use of space, from the probes we’ve sent out to the edge of our solar system to the geo-stationary satellites on which so much of our everyday lives now depend—as well as the launch systems and technology used to get them beyond the Earth’s atmosphere.

“All of this material culture represents the technological stage of humankind at a particular stage of our evolution and history,” insists Dr Beth O’Leary, Professor Emerita in anthropology at New Mexico State University. “The artefacts, and sites are symbolic of the political, social and economic history of the world during this early space age. Although scientific in nature, space archaeologists look also at the meaning and significance of objects and sites. I rank our first lunar landing right up there with the discovery of fire.”

So, if your idea of archaeologists is either Harrison Ford with a whip or of eccentric people spending weeks using small trowels and brushes to uncover artefacts and skeletons buried hundreds or thousands of years, you may well be surprised to learn that some archaeologists are turning their attention to space.

“A good definition of archaeology is the study of the relationships between patterns of material culture and patterns of human behaviour,” she says. “It sets no temporal or spatial limits. It can be done in all times and in all places. Space Archaeology and heritage is the archaeological study of material culture that is relevant to space exploration that is found on Earth and in outer space, and that is clearly the result of human behaviour.”

So why the growing concerns about preservation?

“Archaeology, unlike other disciplines, cannot exist without the material remains of human behaviour,” Dr O’Leary adds. “It is a critical way of understanding human behaviour. The human exploration of space has a material culture that is as relevant to the development of human culture and human evolution as are earliest stone tools 2.5 million years ago. The relevant descriptive data archaeologists collect can be used to answer questions important to prehistory and history.

“Study of the material record, which includes examples of technology, is an essential way to understand how and why humans create and adapt technology to explore even extreme environments such as space. If the material remains are absent, destroyed, looted or not preserved, we lose the ability to understand humans from a unique and important perspective.”

It’s less than 30 years since Brown University archaeologist Richard Gould first proposed that aircraft wrecks might provide important information, laying the foundation for systematic archaeological studies of human flight. As recently as 1993, University of Hawaii anthropologist Ben Finney—who has spent much of his career examining the technology and techniques used by early Polynesians colonisers in the Pacific—suggested that we should start thinking about Russian and American sites on the Moon and Mars. While archaeologists were unlikely to be in a position to conduct proper fieldwork at those sites in the foreseeable future, that didn’t mean they—or unscrupulous treasure hunters—never would!

We know that Armstrong’s footprints and those made by co-astronaut Buzz Aldrin are still there; in 2012 NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) took pictures of the site from just 24km (15 miles) above the surface and confirmed it was essentially as the astronauts had left it—hardly surprising, of course, given that, unlike on Earth, there are no atmospheric conditions to erode or disturb anything.

At the moment, only an extremely unlucky meteorite strike is likely to destroy those unique first human footprints in the lunar dust. However, given that we’re potentially on the verge of a new Space Age that will see both commercial and government missions to the Moon, Dr O’Leary believes that ways must be found to evaluate and preserve such “critical phases of space exploration”. We can’t, in other words, always rely on the Apollo sites being safe from future human activity simply because they’re at least 356,400km (221,456 miles) away from the Earth.

Ironically enough, the biggest challenge space archaeologists face in terms of preservation is legal. “It is a question about who owns space,” Dr O’Leary explains. “According to the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, no nation or state can claim the surface of the Moon or other celestial bodies and space is regulated as a place for peaceful purposes. The Outer Space Treaty also states that the nation or state that puts objects and/or personnel in space or on other celestial bodies maintains responsibility and ownership of such. There is a whole field of space law which by multinational and multilateral agreements regulates (albeit in a piecemeal fashion) the launching and positioning of space vehicles such as satellites. In the research I have done, these agreements and treaties do not address the preservation of cultural resources in space or on any celestial body.

“In 2000, during my work on the Lunar Legacy Project, we contacted NASA and the Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places to nominate the Tranquility Base site on the Moon as a National Historic Landmark,” she adds. “The response from both was that making these part of the US preservation system would be perceived by the international community as a claim of sovereignty over the surface of the Moon, and the Keeper further felt that federal historic preservation law did not have jurisdiction over sites on the lunar surface as they were not on American soil.”

In 2011, NASA recognised the need to address preservation on the lunar surface and included Dr O’Leary in the team which subsequently issued NASA’s Recommendations to Space Faring Entities. However, while several commercial operations have agreed to its guidelines, they are not legally binding. “Space archaeological sites as well as objects—artefacts—fall into a grey legal area as preservation was not seen as an issue when national and international laws and agreements were drafted,” explains Dr O’Leary. “Space and celestial bodies are perceived as a commons.”

Another challenge is that not everything is of archaeological interest, even though most of it is located between 160km (99 miles) and 2,000km (1,200 miles) away in low Earth orbit. Ranging from flecks of paint and metal fragments to spent rocket stages and old satellites, this orbital space debris—while a potential danger to current and future space missions—also contains ‘significant’ objects that warrant protection, such as Vanguard 1, the US satellite launched in 1958 that’s currently the oldest human object in space. “We do not currently have a cohesive way of evaluating the significance of the ‘space junk’,” accepts Dr O’Leary, “which is an obvious first step in considering whether to discard or preserve it.

“Not everything can and should be preserved or considered ‘significant’ and warrant protection,” she adds.“That doesn’t happen on Earth. Frequently in the presence of redundant debris, the debris is sampled and that sample is part of a preservation strategy. Space junk is a serious problem in Low Earth Orbit, but not all space junk is just garbage; there are some historic spacecraft still there that represent the technological, political and social exploration of space. The evaluation of this cultural heritage has barely been considered.”

Some space missions are potentially luckier; there are fundamental mission reasons for locating the new James Webb Space Telescope in an elliptical orbit about the second LaGrange point (so that the gravitation forces of the Sun, Earth and Moon will hold it in a stable location), but this could also ensure the safe survival of the infra-red telescope well beyond its planned lifespan.

However, “future curation” has yet to be included in any space mission plan, even retrospectively. “If there are decisions to be made about what should be destroyed or removed it should be done so that ‘precious artefacts’ should be left in their natural setting given the risk factors for collision or damage,” suggests Dr O’Leary. “These decisions need to informed by the field of space archaeology.

“Governments, commercial entities and university researchers all need to get involved in preservation decisions,” she adds. “There need to be multinational and multilateral cooperative decisions by those space faring entities; the USA, Russia, Japan, the European Space Agency and China have separate and mutual interests in preserving this legacy of wonderful things in order to allow for the study of the Space Age.”

Any readers keen to become the first space archaeologists, however, are already too late. Back in November 1969, Apollo 12 astronauts Charles “Pete” Conrad and Alan Bean landed their lunar module in the Oceanus Procellarum (“Ocean of Storms”), just a few hundred feet from the crater in which unmanned probe Surveyor 3 had soft-landed two and a half years earlier. As part of their mission, the astronauts unintentionally became the first practitioners of extraterrestrial archaeology; they found the remnants of the device, carefully photographed the impressions made by its footpads and then removed the probe’s television camera, remote sampling arm, and pieces of tubing—items which were bagged, labeled and stored alongside the mission’s geological samples.

In 1972, NASA published its Analysis of Surveyor 3 Material and Photographs Returned by Apollo 12, which focused on the ways the retrieved components had been changed by the craft’s voyage through the vacuum of space. The most surprising finding was evidence of the bacteria Streptococcus mitis on part of the camera; eventually, it was concluded that during either launch preparations or subsequent recovery, someone had sneezed on the camera.

If the former, it could be said that space archaeology’s first great discovery could well be that a virus had travelled to the Moon, remained in an alternating freezing/boiling vacuum for two and a half years, and returned promptly to life upon reaching the safety of a petri dish back on Earth—that not even the hostile vacuum of space could stop humans from spreading a sore throat!

EXPERT BIO:

Dr Beth O’Leary

Associate College Professor of Anthropology, New Mexico State University.

For the last 14 years Beth has been involved with the cultural heritage of outer space. With NASA support she has investigated both the archaeological assemblage and the international heritage status of the Apollo 11 Tranquility Base site and was part of a team that created NASA’s Recommendations to Space-faring Entities. She is the co-editor of Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology and Heritage (2009), and Archaeology of the Human Movement Into Space (2014).

TOP 5 SPACE ARCHAEOLOGY SITES

1: SPUTNIK

Baikonur Cosmodrome, Kazakhstan

World’s first artificial satellite.

The actual Sputnik satellite launched by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 burned up on re-entry some three months later, but various replicas and back-up models do survive—ironically, many in the US, the USSR’s Cold War rival. However, the physical results of all the engineering know-how and technological developments which made the launch possible can still be found at the world’s original space launch facility—which remains heavily in use today.

2: VANGUARD 1

Earth Orbit

Oldest human object in space.

US satellite Vanguard 1, launched 17 March 1958, wasn’t a notable first (except in terms of being solar powered) but it has long held the record as the oldest human artefact still in space—nearly 57 years and counting! Originally placed in a 654 by 3,969km (406 by 2,466 miles), 134.2 minute orbit inclined at 34.25 degrees, NASA believes solar radiation pressure and atmospheric drag have reduced its expected orbital lifespan to around 240 years.

3: LUNA 2

Mare Serenitatis, The Moon

First Lunar landing

The USSR’s robotic Luna 2 probe was the first human-made object to “land” on another celestial body (near the Aristides, Archimedes, and Autolycus craters), albeit at speed, and presumably leaving its mark with an impact crater. Luna 2’s known instrumentation—including geiger-counter, magnetometer and micrometeorite detector—confirmed that the Moon had no appreciable magnetic field or radiation belts. But, given this was during the Cold War, was any other technology on board?

4: APOLLO 11 LANDING SITE

Tranquility Bay, The Moon.

First human landing place on the Moon.

According to astronaut Neil Armstrong, Tranquility Bay had “a stark beauty all its own”, but the landing site remains the longest-operating non-terrestrial scientific base—the Laser Ranging RetroReflector (LRRR) left behind by Apollo 11 enables precise measurements of the Moon’s distance from the Earth to be collected to this very day. Frankly, though, it’s also a bit of a mess, with items (such as the LRRR cover) just thrown away by the crew.

5: APOLLO 17 LANDING SITE

Taurus-Littrow valley, The Moon.

Last human landing place on the Moon (for now).

Astronauts Eugene Ceman and Harrison Schmitt spent three days on the surface, collecting samples and travelling almost 36km (22 miles) in their Lunar Roving Vehicle. The abandoned stage of the lunar module includes a plaque signed by the mission’s astronauts and then US President Richard Nixon: “Here Man completed his first explorations of the Moon, December 1972, AD. May the spirit of peace in which we came be reflected in the lives of all mankind.”

LUNAR HISTORICAL PARK?

On 8 July 2013 Congresswoman Donna F Edwards introduced a bill in the House of Representatives—numbered HR 2617—which proposed to “establish the Apollo Lunar Landing Sites National Historical Park on the Moon”, in part to “expand and enhance the protection and preservation of the Apollo lunar landing sites and provide for greater recognition and public understanding of this singular achievement in American history”. The bill also committed the US Department of the Interior to submit the sites to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation) for designation as World Heritage Sites. However, the bill was not brought before the Congress for a vote, in part because of criticism that it could be seen as a claim of US sovereignty over the Moon.

1: MARINER 4

Mars Orbit

First Martian fly-past.

Mariner 4 was the first spacecraft to successfully flyby Mars (on 14-15 July 1965) and send back images of the planet’s surface, although the Moon-like cratered terrain it revealed would prove atypical. For nearly 14 months its distance and antenna orientation halted signal acquisition; by the time this was regained, the gas supply in the attitude control system was exhausted. Shut down on 21 December 1967, Mariner 4 remains in a heliocentric orbit.

2: VIKING 1 LANDER

Chryse Planitia, Mars

First successful lander on Mars

Viking 1 consisted of an orbiter and lander, the latter including two facsimile cameras, three analyses for metabolism, growth or photosyntheses (in the hope of finding life) and other sensors to analyse soil and record pressure, temperature and wind velocity. Contact with the Lander was lost after a faulty command was sent in 1982; the associated Orbiter had already been moved into a higher orbit (preventing a crash until at least 2019) and shut down.

3: HUYGENS PROBE

Titan

First successful landing in outer solar system.

The Huygens probe was the European Space Agency’s contribution to a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to investigate Saturn and its moons; initially attached to NASA’s Cassini probe (the first craft to orbit Saturn and make detailed studies of the planet, its rings and other satellites), Huygens became the first successful, parachute-aided landing (on 14 January 2005) in the outer solar system, and currently remains the most distant landing site for any human made craft.

4: HELIOS PROBES

Solar orbit

Fastest Closest flyby of the sun by any spacecraft.

Helios-A and Helios-B (aka Helios 1 and Helios 2) were a joint venture between then-West Germany and NASA to study solar processes nearer the Sun—in the case of Helios B, from inside the orbit of Mercury. Launched in December 1974 and January 1976, the probes continued to send data up to 1985 and, while no longer functional, remain in their elliptical orbit around the Sun.

5: DEEP SPACE 1

Solar orbit

NASA’s first ion-powered rocket.

Deep Space 1 was the first technology demonstration probe created by NASA’s New Millennium Program; in addition to its payload equipment, the technology demonstrated by the craft included its own xenon ion engine. DS1’s primary and secondary objectives included flybys of near-Earth Asteroid 9969 Braille and Comet 19P/Borrelly. The craft’s ion engines were shut down on 18 December 2001, though its radio receiver was left on in case any future contact is required.

6: VENERA 1

Heliocentric orbit

First spacecraft to flyby Venus.

Launched on 12 February 1961, Venera 1 was the first in a succession of Soviet missions to Venus (Venera 16 ended in 1984); unfortunately, though it became the first human-built spacecraft to fly past another planet the following May, contact had been lost perhaps as early as 5 days into the mission, so no data was received. Rediscovery of the probe, though highly unlikely, could at least cast light on its apparent mechanical failure.

7: NEAR Shoemaker

Near-Earth asteroid Eros

First soft-landing on an asteroid.

Launched in 1996, the Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous – Shoemaker was designed to study the asteroid 433 Eros from close orbit over a period of a year, returning data on its composition, mineralogy, morphology, internal mass distribution and magnetic fields. Despite various software problems, NEAR Shoemaker gathered significant amounts of data before making a successful touchdown on the asteroid. Contact was lost in December 2002; what additional data was found?

8: PIONEER 10 & 11, VOYAGER 1 & 2

Leaving the solar system

First human objects to enter interstellar space.

According to Peter Capelotti, a Professor of Anthropology at Penn State University, there remains a (miniscule) chance these probes, now in interstellar space, might become “archaeological representatives of Homo sapiens to the rest of the galaxy”. Yet they also remain a “snapshot” of humanity at the time of their launch in the 1970s, thanks to the illustrated gold-anodised aluminium plaques on the Pioneers and the gold-plated audio-visual discs attached to the Voyagers.

First published in All About Space Issue 33