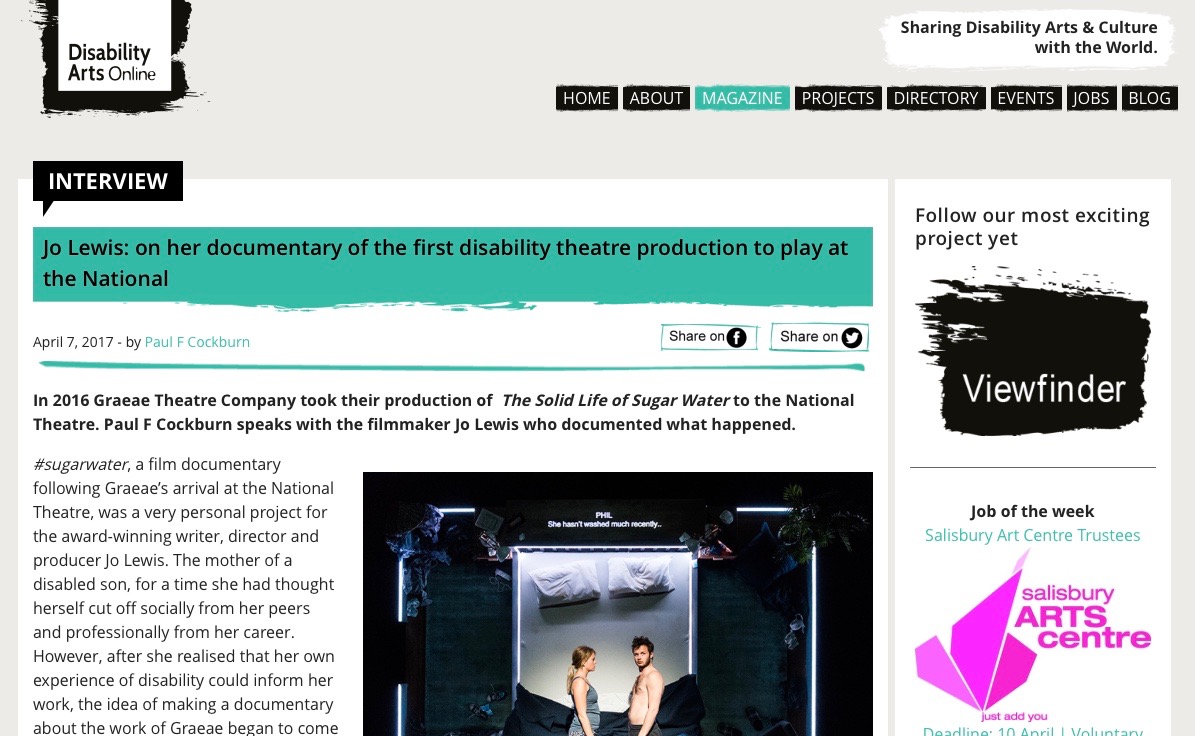

In 2016 Graeae Theatre Company took their production of The Solid Life of Sugar Water to the National Theatre. Paul F Cockburn speaks with the filmmaker Jo Lewis who documented what happened.

#sugarwater, a film documentary following Graeae’s arrival at the National Theatre, was a very personal project for the award-winning writer, director and producer Jo Lewis. The mother of a disabled son, for a time she had thought herself cut off socially from her peers and professionally from her career. However, after she realised that her own experience of disability could inform her work, the idea of making a documentary about the work of Graeae began to come together.

“What is extraordinary about Graeae is that they’re not about shutting doors, of saying you can’t do this and that, or that this is not possible. They’re about opening doors, and asking how we make things possible. I wanted, both on a personal and professional level, to make a film that somehow addressed this, that showed non-disabled people that if you help disabled people have their access requirements met, then there is no disability any more in that sense.”

Jo quickly realised that to cover everything Graeae does would be prohibitively time-consuming and expensive. Luckily there was one specific project on which she could “hook” her documentary. Following a critically acclaimed run during the 2015 Edinburgh Festival Fringe, The Solid Life of Sugar Water by Jack Thorne—best known now for West End hit Harry Potter and the Cursed Child—was about to become the first Graeae production to transfer to a stage at the National Theatre.

“That immediately allowed us to have a focus about what we were doing; it allowed us to have a set time period and a set objective.”

While the documentary ended up being self-funded “for tuppence ha’penny” by her own production company Breakneck Films, the relative intimacy of this particular Graeae show—a cast of two actors—wasn’t a particular factor in Jo choosing to focus on the production.

“It was just that it was clear from the outset that Sugar Water was the most brilliant play. What I liked about it was that it sort of made disability both relevant and irrelevant at the same time; the performers have a disability, but they were so good that actually the disability wasn’t really an issue. Equally, the characters’ experiences are very universal; either by having children, or knowing people who have children, most audiences will be able to connect with the characters in some way, shape or form. As a filmmaker, it ticks a lot of boxes. I’m trying to reach out, with this film, to as many people as possible; there was enough about everything that was going on to help with the connection rather than limit it in any way.”

The documentary was shot during a two month period, and includes some footage of actors Genevieve Barr and Arthur Hughes working with director Amit Sharma—though this was far from being their first days of rehearsals.

“They’d had a break of about six months after Edinburgh, which is long enough in theatre terms for them not to be starting from scratch, but to be reconnecting with the material. I think the very early stages of the cast ‘finding character’ possibly isn’t that interesting to an audience—my audience, anyway. This allowed me to give a sort of insight into the rehearsal process without the film being about just the rehearsals. I wanted the film to be about taking a show and putting it on a massive stage—one of the biggest theatres of them all, in terms of prestige—and the challenges that they faced as performers and as a company. And also seeing the National Theatre grow and learn and react to the experience as well.”

Jo is the first to say how helpful everyone was, at both Graeae and the National Theatre, during and following filming.

“We had complete open access. Graeae really trusted us: their Artistic Director Jenny Sealey knew that I had a personal connection with disability, and that my intention was to make a film that would inspire disabled people to take to the stage and to educate non-disabled people in some of the issues that disabled people face. The trust was there from the beginning and we were allowed to film anything, anytime, anywhere.

“That was quite important; you can’t make a very open, honest fly-on-the-wall documentary if people are trying to dictate the agenda. We weren’t trying to make a piece of PR for either the National or Graeae; we were trying to make an objective film that showed the problems and challenges in a really honest and open way. Graeae were really cool about that, actually. And so were the National. They were incredibly supportive and incredibly kind,”

The biggest challenge was, ultimately, the editing.

“We came away with hours and hours of footage, all of it gold dust. We had to really define and work out what we didn’t want to include. In that sense, the only real challenge for me as a filmmaker about this whole process was the navigation through the edit. I was very lucky; I was working with a fabulous editor; Adam Gough gave me all the time in the world to get the film ‘right’. The length of this film found itself and, having watched it now at the premiere, it feels a good length.”

Disabled arts have been particularly affected by years of austerity-inspired cuts, a subject the film doesn’t ignore.

“Being the mum of a disabled child, I know what a nightmare getting formal monetary support can be. I didn’t seek out that as a backdrop, but I welcomed it when it arose because it is a very real problem. Vital funds that allow a lot to happen are being strangled and cut-off in an appalling way. I wasn’t trying to make a film that preached, or to make an overtly ‘political’ film, but these issues are part of the everyday life experience of being a disabled person. You can’t really talk about disability without referring to them.”

First published by Disability Arts Online.