Last November, the film and video artist John Smith became the latest recipient of the annual Film London Jarman Award. Smith, who has already built-up an internationally recognised body of work, follows in the steps of, among others, 2012 Turner Prize nominee Luke Fowler, who won the inaugural Jarman Award in 2008.

“The breadth and scope of the artists in the shortlist was fascinating to consider and made for a rich and exciting discussion,” according to a statement from the 2013 jury. “In choosing the winner we returned to the essence and spirit of Derek Jarman himself, as a British filmmaker with a love for experimentation, pageantry, and his borderless approach to disciplines–he was transgressive.”

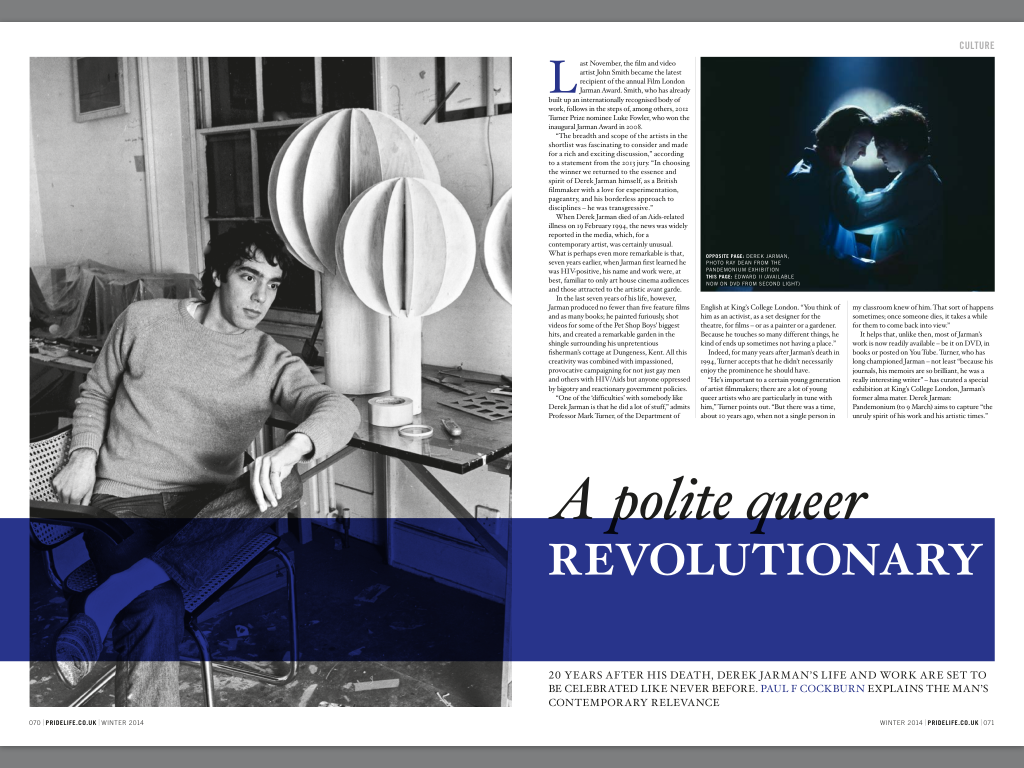

When Derek Jarman died of an AIDS-related illness on 19 February 1994, the news was widely reported in the media; which, for a contemporary artist, was certainly unusual. What is perhaps even more remarkable is that, seven years earlier, when Jarman first learned he was HIV positive, his name and work were at best familiar to only art house cinema audiences and those attracted to the artistic avant garde.

In the last seven years of his life, however, Jarman produced no fewer than five feature films and as many books; he painted furiously, shot videos for some of the Pet Shop Boys’ biggest hits and created a remarkable garden in the shingle surrounding his unpretentious fisherman’s cottage at Dungeness, Kent. All this creativity was combined with impassioned, provocative campaigning for not just gay men and others with HIV/AIDS but anyone oppressed by bigotry and reactionary government policies.

“One of the ‘difficulties’ with somebody like Derek Jarman is that he did a lot of stuff,” admits Professor Mark Turner, of the Department of English at King’s College London. “You think of him as an activist, as a set designer for the theatre, for films–or as a painter or a gardener. Because he touches so many different things, he kind of ends up sometimes not having a place.”

Indeed, for many years after his death in 1994, Turner accepts that Jarman didn’t necessarily enjoy the prominence he should have. “He’s important to a certain young generation of artist filmmakers; there are a lot of young queer artists who are particularly in tune with him,” Turner points out. “But there was a time, about 10 years ago, when not a single person in my classroom knew of him. That sort of happens sometimes; once someone dies, it takes a while for them to come back into view.”

It helps that, unlike then, most of Jarman’s work is now readily available–be it on DVD, in books or posted on You Tube. Turner, who has long championed Jarman–not least “because his journals, his memoirs are so brilliant, he was a really interesting writer”–has curated a special exhibition at King’s College London, Jarman’s former alma mater. Derek Jarman: Pandemonium (23 January-9 March) aims to capture “the unruly spirit of his work and his artistic times.” It’s just one of many celebrations of Jarman’s work in the coming months.

A sense of what was to come came towards the end of 2013, when the Wilkinson Gallery in London brought together a significant number of his paintings in a show now headed for the Trondheim kunstmuseum in Norway. “I think he’s a really great artist,” explains the gallery’s director, Amanda Wilkinson. “His paintings haven’t received as much recognition as the films, so we wanted to correct that. They’re really passionate–sometimes very tender, sometimes very sad, sometimes very angry.”

The response to the exhibition was extremely positive. “I think he’s really revered by young artists,” Wilkinson adds. “We could see that by the number of young art students coming to the gallery, and lots of people writing notes about how much it means to them and how important his work is to them.”

The breadth of that work is itself significant. ““Nowadays, it’s unusual to say ‘Oh, an artist does only this.’ Artists do lots of different things within their practice, so I think his work was a precursor to that,” Wilkinson says. “He was very aware of everything contemporary around him, whether it was visually or politically; he absorbed it and translated it in his own visual language in such a special way.”

Back in the 1980s, that included the bad as well as the good. It’s likely that Jarman learned of his HIV positive status while making The Last of England. “That’s his kind of ‘Condition of England’ film, his ‘state of the nation’ film,” says Mark Turner. “It’s his concerted attack at Thatcher, though I don’t think she’s ever mentioned as such. It’s one of his most personal films–he puts his home movies into it–but there’s a kind of personal turn, I think, where his own situation becomes important politically.”

Arguably, Derek Jarman was the first UK public figure to come out as HIV positive, at a time the virus was denounced as the ‘gay plague’ and people with HIV were demonised by tabloid newspapers and right-wing MPs. “I invited him to speak at the world’s first-ever ‘AIDS & Human Rights’ conference,” says long-term equality campaigner Peter Tatchell. “Derek’s speech was incredibly moving and powerful.

“He voiced the belief of many people with HIV–and their non-HIV allies–that governments had to shift the focus from denial, indifference, scapegoating and repression to education, prevention, treatment and support. His words and our conference helped begin to shift the consensus towards greater compassion and enlightenment with respect to HIV.”

Jarman also joined in the work of rights group OutRage! “He never acted like a diva or queen bee,” Tatchell insists. “He just slipped in alone, mingled and contributed ideas along with everyone else.” Nevertheless, his involvement could prove extremely useful–not least when he and more than 50 protestors were arrested on a march on Parliament. “He was a bit of a celebrity, so that gave our campaigns a much higher public profile than we may have otherwise achieved.

“He was irreverent, rebellious, questioning and radical–not at all cosy and comfortable,” Tatchell insists. “He never sought the establishment’s embrace or approval. He loathed the power elite and all they stood for. He didn’t like Stonewall’s uncritical aspiration to mere equality within the status quo. Like me, he wanted to change society, but Derek’s subversive ideas were always expressed gently. He was a polite queer revolutionary, with the knack of being able to express radical, challenging ideas in the most charming manner.”

That was as true of his art as his politics, assuming the two can be truly separated.“At the time, he was an important figure for working outside the system,” insists Mark Turner. “Since then, we’ve started to discover things like the writing more. Virtually everything he’s written is now in print–and that says something, because publishers have no desire to keep you in print for nostalgic reasons. I would say he’s still important, and I know young important artists today who are absolutely in his… not his image, but his lineage, who pay a debt to him.”

Jarman 2014

A year-long celebration of his life and work.

www.jarman2014.org

Derek Jarman: Pandemonium

Inigo Rooms, Somerset House East Wing, Strand, London WC2R 2LS

23 January–9 March 2014, 12.00–18.00 daily (until 20.00 on Thursdays)

Admission Free.

www.kcl.ac.uk/cultural

First published in Pride Life #15 Winter 2014.