To the Cunard board that had commissioned her, the new liner was simply designated Q4, the fourth class of “Queen” to join the Cunard passenger fleet. At John Brown’s Shipyard, Clydebank, where some 3,000 men spent two years constructing the 58,000-ton liner, she was “No 736 express passenger liner”. Neither, of course, were destined to be painted on her bow; that was only revealed when she was launched by HM The Queen on 20 September 1967.

The previous evening, though, many Clydesiders—or at least those willing to put money on it—believed that the new vessel was going to be a “Princess”, following the 11th hour inclusion of the Queen’s younger sister, Princess Margaret, among the royal party attending the launch. Bookie John Banks of Glasgow told the press that he had been forced to shortened the odds on “Princess Margaret” from 25-1 to 4-1, making her almost joint favourite with wartime Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill.

Other popular choices included “Prince Charles” (4-1), Princess Anne (6-1) and—another indicator of the time—“John F Kennedy”, after the assassinated American President (also 6-1). According to Mr Banks, some 12,000 bets had been placed, totalling more than £3,000. That was quite a lot of money back in 1967; though not, admittedly, on the scale of the £24 million loan to Cunard from the UK Government to cover most of the ship’s estimated £29 million cost.

On the day, some 30,000 people gathered at Clydebank to hear the monarch name the ship after herself: “Queen Elizabeth the Second”. This proved good news not just for John Banks, who felt obliged to donate his £400 profits to a naval charity, but also the few who had gambled on the name’s seemingly poor odds of 14-1.

Yet some confusion remains, not helped by Cunard’s later decision to paint “Queen Elizabeth 2” rather than the traditional regnal “Queen Elizabeth II” on the bow. Was she simply the second Cunard vessel to be named “Queen Elizabeth”, or was Her Majesty right to assume, with Cunard already operating vessels named after her grandmother and mother, that Q4 was rightfully “hers”?

Not that the launch went without incident. After the Queen named the ship—repeating the “God speed” message after the first attempt was drowned out by the cheering crowd—she cut the ribbon holding the traditional bottle of champagne and pressed the button controlling the release mechanism. The ship moved a fraction of an inch, then stopped.

Seconds slowly passed. Typical of the West Coast, someone in the crowd shouted: “Gie us a shove!” Briefly, it looked as if bowler-hatted George Parker, the shipyard’s director, was about to do just that, as he climbed onto the small platform alongside the ship’s cradle. But then, after more than a minute, gravity took hold and the vessel slid slowly but surely down into the water, “with little more than a discreet flurry of creamy spume,” according to one reporter.

For the then-Secretary of State for Scotland, William Ross, the new vessel was nothing less than “the latest and greatest achievement of the Clyde shipbuilders,” and a sign that “this river of great ships still produces the best. The skill and craft and courage that have made this great ship will be carried into the new era on the Clyde. Wherever people look for quality in ships, they will still find it in the proud label—‘Clydebank built’.”

In hindsight, such talk of a “new era on the Clyde” feels at best wishful thinking; QE2 was the last vessel launched from John Brown’s before the company was merged with five others to form Upper Clyde Shipbuilders Ltd, which collapsed amidst much controversy just four years later. Yet, at the time, there was still optimism, according to Hugh Morrison, who started as an apprentice draftsman back when the keel of the QE2 was laid down in 1965.

“The QE2 was seen as one of the milestones of recovery from the Second World War,” he says. “We had the Mini car, Carnaby Street and the Beatles; Concorde was on the go. The thought of building a new ‘Queen’ was symbolic of British shipping again coming to the forefront. When I joined in August 1965, there were six ships building at the same time on Clydebank, a post-war high-point for the yard.”

Certainly, there was still plenty of work to be done on the QE2 after the launch in September 1967; John Brown’s took on around 500 additional tradesmen to fit out the ship, while Hugh and his peers were kept busy drawing up an “operations manual” for the vessel’s captain and crew—so they knew how to balance its cargo, for example. However, Hugh accepts that British shipbuilding, and the Clyde in particular, were being overtaken by the likes of Germany and Japan. “We were being left behind; a lot of the equipment they had in the yards, especially Clydebank, was antiquated. These great big cranes you see could only lift 15 tons, which is nothing.

“The other yards had losses too, while John Brown’s had taken on the QE2 at a price that was something next to stupid. They had this idea in their head that what they possibly lost in money they would gain in prestige, which is an unrealistic way of doing business.”

That said, by the time Hugh and his peers had finished their apprenticeships, they found the world very interested in them. “Working on a big passenger ship like the QE2 actually earns you a wealth of knowledge. Many people like us had real practical knowledge that, if the Clyde didn’t want to use, other shipyards did.”

Hugh’s subsequent career took him to the big shipyards in Germany and Holland before eventually ending his career at Lloyds Register in London, but the Clyde has never entirely left him. “When they started the QE2 they took on a lot of apprentices because they knew there’d be a lot of what they considered ‘menial’ design work,” he explains. “There were 15 of us when we started in August 1965, and all but two—who are dead now—are still in contact. We’ve actually had two reunions in the past four or five years.”

. . .

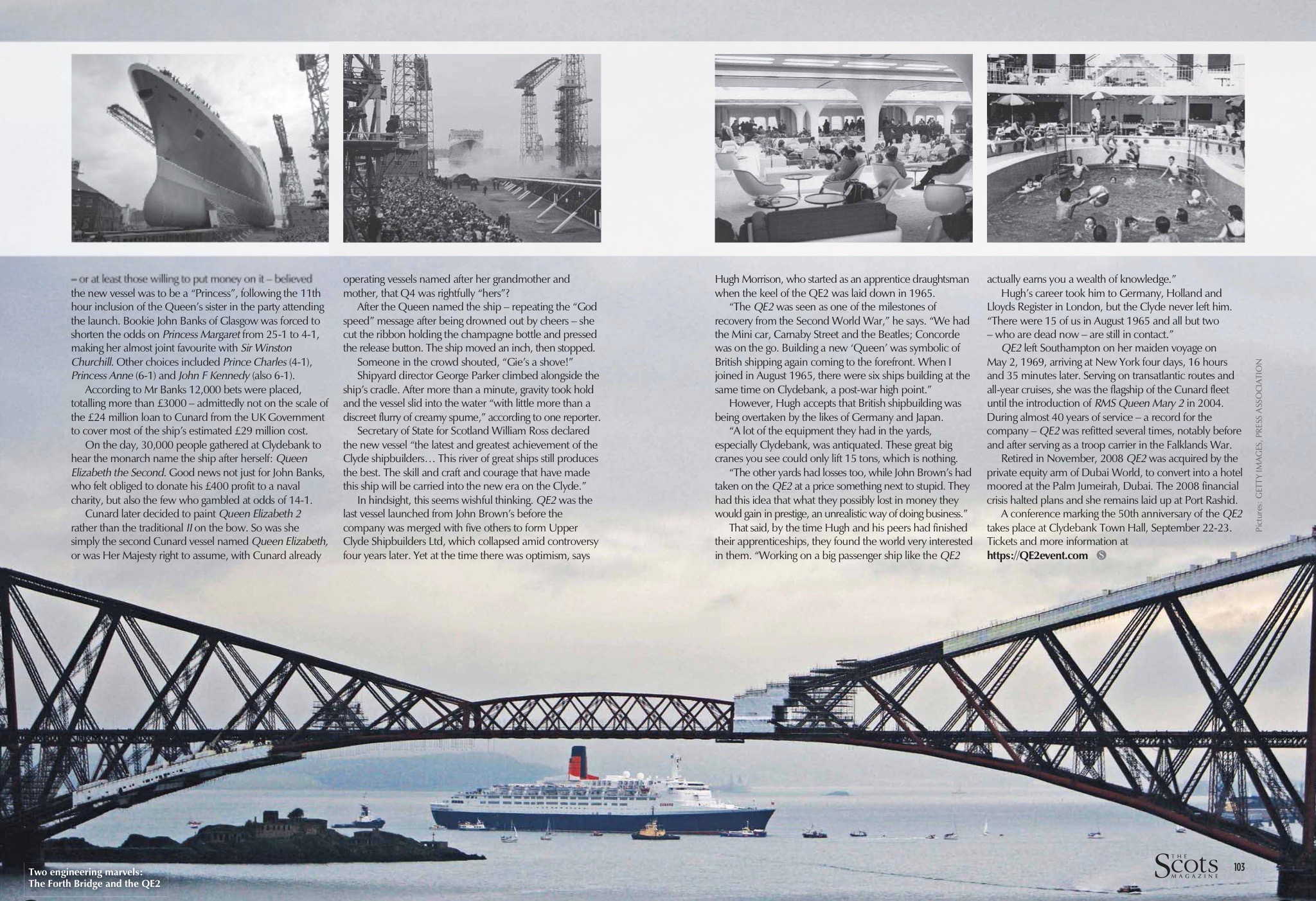

The QE2 departed Southampton on her maiden voyage on 2 May 1969, arriving at New York four days, 16 hours and 35 minutes later. Serving on both transatlantic routes and all-year cruises, she was the flagship of the Cunard fleet until the introduction of RMS Queen Mary 2 in 2004. During almost 40 years of Service—a record for the company—QE2 was refurbished and refitted on several occasions, notably before and after serving as a troop carrier during the Falklands War in 1982.

The QE2 departed Southampton on her maiden voyage on 2 May 1969, arriving at New York four days, 16 hours and 35 minutes later. Serving on both transatlantic routes and all-year cruises, she was the flagship of the Cunard fleet until the introduction of RMS Queen Mary 2 in 2004. During almost 40 years of Service—a record for the company—QE2 was refurbished and refitted on several occasions, notably before and after serving as a troop carrier during the Falklands War in 1982.

QE2 was retired from active Cunard service on 27 November 2008, and acquired by the private equity arm of Dubai World, which planned to convert the ship into a 500-room floating hotel moored at the Palm Jumeirah, Dubai. The 2008 financial crisis, however, halted plans and the ship remains laid up at Port Rashid, with several subsequent conversion plans so far coming to nothing.

. . .

A special conference marking the 50th anniversary of the QE2 takes place at Clydebank Town Hall, 22-23 September. Tickets and more information can be found here.

First published in The Scots Magazine, #September 2017.