20 years after his death, why is the filmmaker, artist, writer and campaigner so revered?

“I think he’s a really great artist, important in so many ways,” says Amanda Wilkinson, director of the Wilkinson Gallery in London which, in the latter part of 2013, hosted an exhibition of Derek Jarman’s “black paintings” which is now about to open at the respected Trondheim kunstmuseum in Norway.

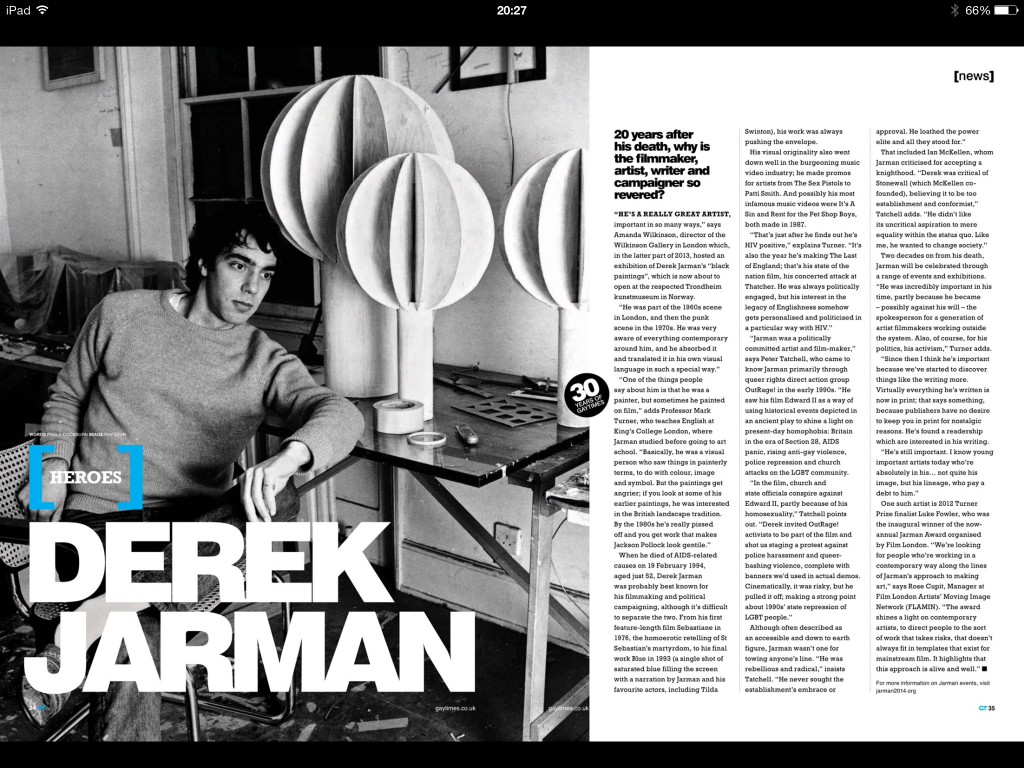

“He was part of the 1960s scene in London, and then the punk scene in the 1970s. You can see there’s an influence there, although I don’t think it should be overplayed. I think he was very aware of everything contemporary around him, whether it was visually or politically; he absorbed it and translated it in his own visual language in such a special way.”

“One of the kind of things people say about him is that basically he was a painter, but sometimes he painted on film.” adds Professor Mark Turner, who teaches English at King’s College London, where Jarman studied before going to art school. “Basically, he was a visual person who saw things in painterly terms, to do with colour, to do with image, to do with symbol. But the paintings get angrier and angrier; if you look at some of his earlier paintings, he was interested in the British landscape tradition. By the 1980s he’s really pissed off and you get work that makes Jackson Pollock look gentile.”

When he died of AIDS-related causes on 19 February 1994, aged just 52, Derek Jarman was probably best known for his filmmaking and political campaigning, although it’s difficult to separate the two. From his first feature-length film, the homoerotic retelling of St Sebastian’s martyrdom Sebastiane in 1976 (the first film to be recorded with all-Latin dialogue) to his final work Blue in 1993 (a single shot of saturated blue filling the screen with a narration by Jarman and his favourite actors, including Tilda Swinton), his work was always pushing the envelope.

His particular visual originality also went down well in the burgeoning music video industry; he made promos for artists ranging from The Sex Pistols and Throbbing Gristle to Marianne Faithfull and Patti Smith; possibly his most infamous music videos were It’s A Sin and Rent for the Pet Shop Boys, both made in 1987.

“That’s just after he finds out he’s HIV positive,” explains Turner. “It’s also the year that he’s making The Last of England; that’s his state of the nation film, his concerted attack at Thatcher, though I don’t think she’s ever mentioned as such. He was always politically engaged, but his interest in the legacy of Englishness somehow gets personalised and politicised in a particular way with HIV.”

“Jarman was a politically committed artist and film-maker,” says Peter Tatchell, who came to know Jarman primarily through queer rights direct action group OutRage! in the early 1990s. “He saw his film Edward II as a way of using historical events depicted in an ancient play to shine a light on present day homophobia: Britain in the era of Section 28, AIDS panic, rising anti-gay violence, police repression and church attacks on the LGBT community.

“In the film, church and state officials conspire against Edward II, partly because of his homosexuality,” Tatchell points out. “Derek wanted to give the film an added, explicit contemporary feel and relevance. He invited OutRage! activists to be part of the film and shot us staging a protest against police harassment and queer-bashing violence, complete with real banners that we’d used in actual demos. Cinematically, it was a risky switch from the past to the present and back, but he pulled it off; making a strong point about 1990s’ state repression of LGBT people.”

Although often described as an accessible and down to earth figure, Jarman wasn’t one for towing anyone’s line. “He was irreverent, rebellious, questioning and radical–not at all cosy and comfortable,” insists Tatchell. “He never sought the establishment’s embrace or approval. He loathed the power elite and all they stood for.”

That included the likes of Ian McKellan, whom Jarman publicly criticised for accepting a knighthood. “Derek was critical of Stonewall [which McKellen co-founded–Editor], believing it to be too establishment, tame, assimilationist and conformist,” Tatchell adds. “He didn’t like its uncritical aspiration to mere equality within the status quo. Like me, he wanted to change society.”

Two decades on from his death, Jarman will be celebrated through a range of events, exhibitions and retrospectives. “I think he was incredibly important in his time, partly because he became–possibly against his will–the spokesperson for a generation of artist filmmakers working outside the system. Also, of course, for his politics, his activism; he would be the person who would fetch up on television and get pissed off about what was happening, and not always in ways that made people comfortable.

“Since then I think he’s important because we’ve started to discover things like the writing more,” Turner adds. “Virtually everything he’s written is now in print; that says something, because publishers have no desire to keep you in print for nostalgic reasons. He’s found a readership which are interested in his writing. Though I think the internet has helped spread his work. YouTube is completely conducive to disseminating his short films.”

“I would say he’s still important. I know young important artists today who are absolutely in his… not quite his image, but his lineage, who pay a debt to him.”

One such artist is 2012 Turner Prize finalist Luke Fowler, who was the inaugural winner of the now-annual Jarman Award organised by Film London. “We’re looking for people who are working in a contemporary way along the lines of Jarman’s approach to making art,” says Rose Cupit, Manager at Film London Artists’ Moving Image Network (FLAMIN). “The award shines a light on contemporary artists, to direct people to the sort of work that takes risks, that transgresses, that doesn’t always fit in the templates that exist for mainstream film. It highlights that this approach is alive and well.”

For more information on Jarman events, check www.jarman2014.org.

First published by GT (Gay Times) #429 (February 2014).