Niche, it appears, is king when it comes to successful magazines. According to the people at Magazine Publisher, “poor magazine focus” and “lack of focused editorial concept” are as fatal to a title’s chances as overestimated circulations and a lack of financial backing.

Niche, it appears, is king when it comes to successful magazines. According to the people at Magazine Publisher, “poor magazine focus” and “lack of focused editorial concept” are as fatal to a title’s chances as overestimated circulations and a lack of financial backing.

But it would appear that, sometimes, you can be too niche.

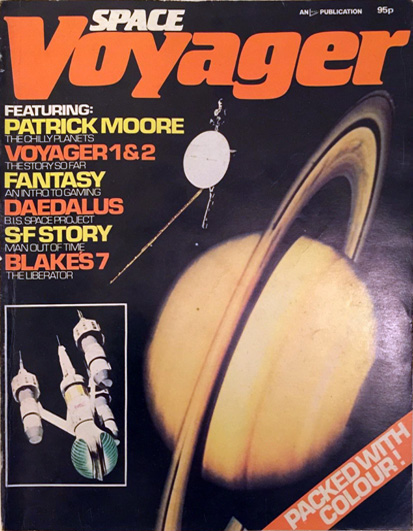

Space Voyager

Space Voyager is one of those 1980s magazines which, despite me never being a regular reader, now inspires a lot of nostalgia. There were a total of 18 issues; a debut “issue zero” testing the water in 1981, and then 17 numbered issues, the last published in early September 1985. Issues 1-4 were published quarterly under the slightly revised title New Voyager, and subtitled: “Today’s magazine for those who can’t wait for tomorrow”. By “Tomorrow”, the editors clearly meant future space missions, forthcoming films, and TV shows (both current and what would now be termed “cult” or “classic”). Oh, and model-making: specifically models linked to either actual human space flight or SF films/TV shows.

If that seems a strange combination, it was likely down to the interests of the two men who launched the title–Ray Rimell (who took on the role of managing editor) and Mat Irvine (as technical editor). The latter is probably still best remembered by a generation of British TV viewers as the long-haired guy who turned up regularly on Multi-Coloured Swap Shop to explain how he made spaceship models for Blake’s 7, Doctor Who and The Sky at Night.

Of course, the choice of publisher also was a major factor. Model & Allied Publications Ltd (MAP) had started just after the Second World War, publishing a range of modelling magazines and books including Aeromodeller. Bought by Argus Press in the mid-1970s, by the time Space Voyager appeared the company must have had the UK’s largest portfolio of specialist modelling magazines (covering military, car, aircraft and boat modelling) as well as titles on photography, woodworking, wine-making and home brewing, and several computing-related titles.

Perhaps Rimell and Irvine pitched Space Voyager as a space-modelling title, but the former certainly appeared to be convinced that there was “a real need for a high quality British science fiction/fact magazine”. Early on, he’d been gratified (and relieved too, no doubt) by the largely positive feedback from readers. Yet, neither Rimell nor Irvine would stay with the title past its sixth issue, by which time it had reverted to Space Voyager, albeit with a promising shift from a quarterly to a bimonthly schedule.

Evolutionary change, not revolutionary.

New editor Ian Graham officially took over the reins with issue 8, which proved something of a relaunch; a largely new editorial and production team listed on the contents page, and a rebranded publisher too–Argus Specialist Publications Ltd. Some things, though, remained unchanged; not least a general preference for covers–and some internal features–illustrated by the acclaimed space artist David Hardy. There also remained the factual articles by television’s most famous amateur astronomer, Patrick Moore.

Arguably, Moore provided the only continuity throughout the magazine’s entire run; his name often prominently on the cover, the last four issues credited him as “Consultant Editor” just below the title.

I’m afraid I have no idea how well the magazine sold, but one thing which stands out now is just how little advertising it carried. In my own professional experience, most newsstand magazines aim for a 60/40 split between editorial and advertising. Space Voyager, however, always staggered perilously on the wrong side of a 90/10 split. This clearly was a factor in Graham’s departure after issue 11; in his final editorial, he even made the point of writing:

Space Voyager is an odd creature in the magazine business. It covers a wide range of loosely connected topics, each of which has an extremely enthusiastic following. However, most of those topics don’t lend themselves to attracting advertisers, which every magazine must do to survive. (…) Moreover, because the magazine covers a wide range of topics, it’s difficult to ‘pigeon hole’ as a spaceflight magazine, or an SF magazine or a modelling magazine, etc, etc. It’s all of those things and many more, but not any one of them exclusively. And that makes it a difficult magazine to which to assign a convenient identity for the purposes of selling advertising.

In other words, Space Voyager was actually proving too niche for its own good; its ideal “golden customers” (those offering the best return for the least effort) were in the small portion of a complex 3D Venn Diagram where space fact, fantasy, SF, modelling, computing and a few other topics somehow all managed to overlap.

That said, those readers were still potential reasons for companies to advertise in the magazine; that this didn’t happen rather suggests to me that Space Voyager didn’t receive a sufficient investment of time and passion from the publisher’s advertising executives. (I know from personal experience that the high quality of a magazine doesn’t make a damned difference if you don’t have advertising coming in to support the publication.)

Lacking direction

Graham’s successor, former contributor (and no relation, as they both kept insisting), Wendy Graham also recognised that the magazine was “a rag-bag of overlapping interests”; she suggested that this was actually part of Space Voyager’s charm. Yet the results of a readers’ survey (launched in issue 15) showed that even the people buying the magazine (and willing to fill in survey forms) felt it “lacked direction” and was “trying to be all things to all men”. The conclusion: Space Voyager should have more science fiction (including original short stories), more science fact, less modelling and less stuff on conventions and fandom.

My gut feeling is that Wendy Graham was certainly willing to shift the magazine in this direction. She wasn’t given the opportunity, however; issue 17 came with a new editorial byline. In his first – and last – editorial for the magazine, Peter Chrisp wrote that Graham and assistant editor Chris Richmond had “moved on to pastures new” – a clear sign that they were fired – but he promised that their work could well turn up in future issues. (The significant change in contributors also suggests that the team Graham and Richmond had built up over the last few issues had “walked out” in sympathy.)

Chrisp certainly appeared confident about the direction the magazine was headed, and there was still that regular “Next issue” box towards the back of the magazine, on this occasion promising–among other things–a new short story, a feature on astronomy in Canada and an interview with the one and only Harlan Ellison.

However, just as NASA’s Apollo 18 was cancelled before it got anywhere near the launch pad, Chrisp was never given an opportunity to even say goodbye in print. Issue 18 simply never appeared.

Then and now

Did Space Voyager have much impact on subsequent UK magazines? I’m not entirely sure. Its failure to survive might suggest that there are very good reasons why today our newsstands clearly distinguish between science fiction (by which I mean mostly TV and films) and science fact.

Patrick Moore presumably learned a few lessons from his involvement with Space Voyager which might have influenced how he approached Astronomy Now (which he co-founded in 1987, and initially edited) and later BBC Sky at Night Magazine.

I have no idea whether that Harlan Ellison interview happened or ever saw the light of day, but it would have been the latest in a run of interviews with famous SF authors – Douglas Adams (#13), Frank Herbert (#14), Terry Pratchett (#15), Brian Aldiss (#16) and Arthur C Clarke (#17) – by a young, up-and-coming journalist by the name of Neil Gaiman. Yes, that Neil Gaiman.

I do know, though, that is Gaiman hadn’t first met Pratchett courtesy of that interview, it’s unlikey they would have gone on to write Good Omens together – and who knows how Gaiman’s career might have turned out then!